When you think of bacteria, you probably think of microscopic organisms too small to be seen by the naked eye. In fact, even the largest bacteria is barely visible without the use of a microscope. However, while all bacteria are incredibly small, certain species still stand out from the rest as being unusually large.

Today we’ll be taking a look at 5 of the largest kinds of bacteria in the world, and learning a little bit about what makes each one different. What unique features set these special (and sometimes deadly) organisms apart from each other? Let’s find out!

-

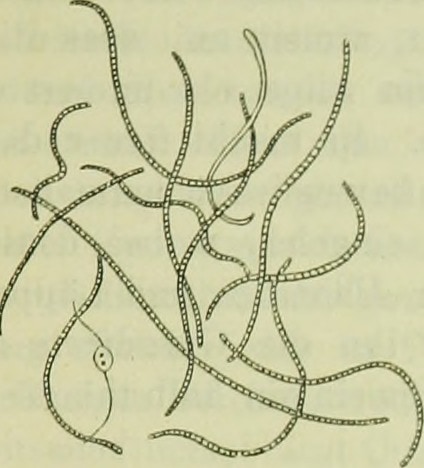

Oscillatoria princeps

Year Discovered: 1892

Discovered by: Vaucher ex Gomont

Shape: Long and cylindrical

Source: wikimedia.org

The Oscillatoria genus of filamentous cyanobacteria includes over 100 different species. This genus is also referred to as “blue-green algae,” or oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Blue-green algae inhabits fresh, marine, and brackish waters. Oscillatoria princeps is a symbiotic variety, and only reproduces asexually or through fragmentation or spore formation, like various species of flora can.

Did You Know?

When blue-green algae rapidly reproduce on the surface of the water, or “bloom,” they sometimes release toxins. A toxic algae bloom can cause severe illness or death in animals that drink contaminated water, or come into contact with the algae.

-

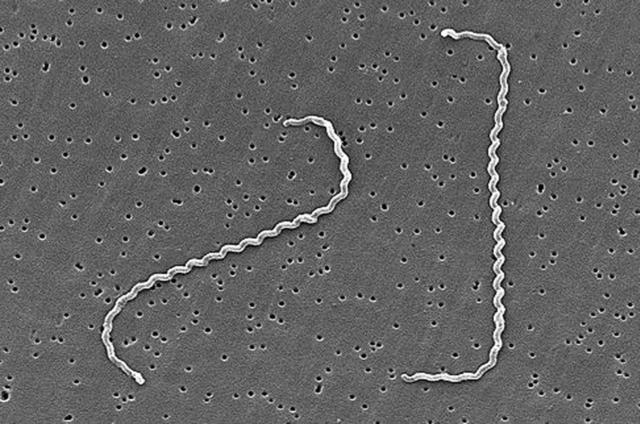

Spirochaeta plicatilis

Year Discovered: 1835

Discovered by: C.G. Ehrenberg

Shape: Long, helically coiled

Source: flickr.com

This species of bacteria is believed to be nonparasitic, often inhabiting aquatic environments, and able to survive in both freshwater and saltwater. Spirochaeta plicatilis sports 18-20 periplasmic flagella on either end of its body, which wind around the spiral-shaped structure to create a unique method of movement.

Did You Know?

Spirochaeta plicatilis’ unique flagella give it the ability to traverse surfaces as gliding bacteria do, along with giving it an advantage in the water. This bacteria can make its way through higher-viscosity liquids than other varieties as well.

-

Leptospira interrogans

Year Discovered: 1915

Discovered by: Ryokichi Inada and Yutaka Ido

Shape: Long, helically coiled

Source: wikimedia.org

Spirochetes can sometimes reach up to 500 µm in length, and most prefer an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment. Leptospira interrogans in particular thrives within animals’ bodies, away from the dry air. This bacteria causes Leptospirosis, or “Swineherd’s Disease,” an acute systemic illness that inflames the blood vessels. While this disease primarily affect animals, it can still be transmitted to humans.

Did You Know?

Climate is a prominent factor in this bacteria’s ability to flourish–outbreaks of Leptospirosis are most common in tropical areas. For example, this disease has sprung up in areas such as Brazil, India, and Southeast Asia in recent years.

-

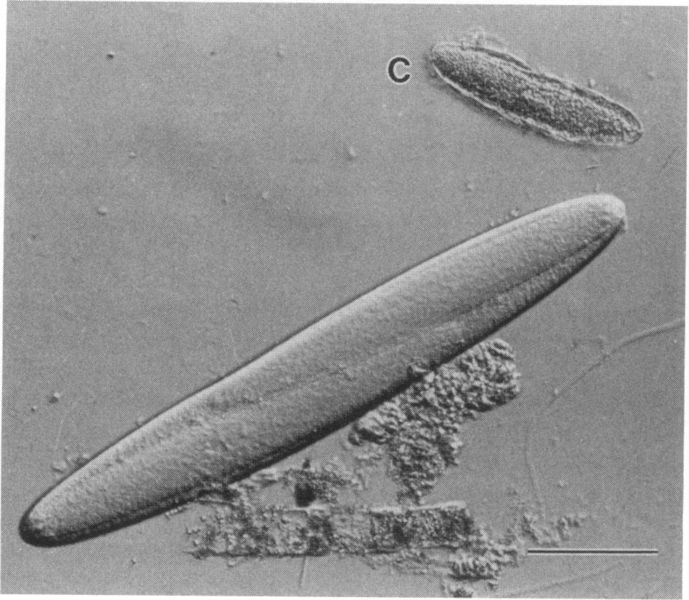

Epulopiscium fishelsoni

Year Discovered: 1985

Discovered by: Lev Fishelson

Shape: Elliptical

Source: wikimedia.org

The cell size of Epulopiscium fishelsoni varies more than that of any other bacteria. Mainly found in the waters of the Red Sea and the coastal waters of Australia, these bacteria are so massive that they were thought to be protists for years after their discovery.

At a whopping 600 µm in length, the largest specimens of Epulopiscium fishelsoni were originally discovered in the intestinal tracts of Brown Surgeonfish. The bacteria and several varieties of Surgeonfish share a symbiotic relationship, with the bacteria aiding in the digestion of algae and detritus.

Did You Know?

The name “Epulopiscium” means “guest at a banquet of a fish”.

-

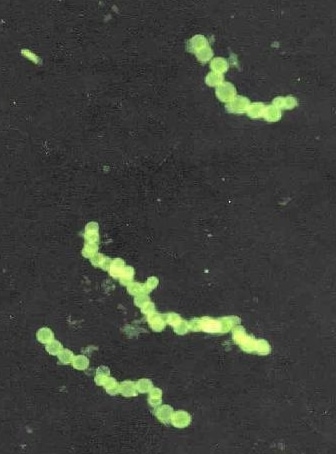

Thiomargarita namibiensis

Year Discovered: 1997

Discovered by: Heide Schulz and research team

Shape: Chain of cocci

Source: wikimedia.org

Thiomargarita namibiensis is the largest bacteria in the world. This bacteria is found among the sediments of the continental shelf of Namibia, Africa. At 0.75 millimeters wide, it is large enough to see with the naked eye. The name Thiomargarita means “sulfur pearl,” in reference to the appearance of the bacterial strands.

Did You Know?

Heide Schulz reported that her fellow researchers didn’t believe her when she announced the size of the bacteria, but that she instantly recognized what she saw as sulfur bacteria. She and her team were from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology.